Readers: Two centuries ago, human kind was not capable of creating deadly diseases. They just didn’t possess the scientific knowledge to intentionally produce a disease that could slaughter millions of people. You may have noticed that I have not published an article for two weeks. The Chinese/Fauci Flu, created using YOUR tax dollars, finally arrived at my house; therefore, I was too weak to research & write. Below is an article I wrote for local papers some months ago. You will find these details about medical care “in olden days” most interesting. Diane

When reading the letters, journals & diaries of generations past one discovers that, not only was the world they inhabited profoundly different from our own, but they viewed life & death much differently. Before he even came of age, Meriwether Lewis lost his father (pneumonia) and his step-father (cause lost to history). No wonder his letters, even business letters, invariably began with an inquiry into the health of the recipient and closed with an assurance that his own health was fine. Remarks about health could likewise be found in William Clark’s letters.

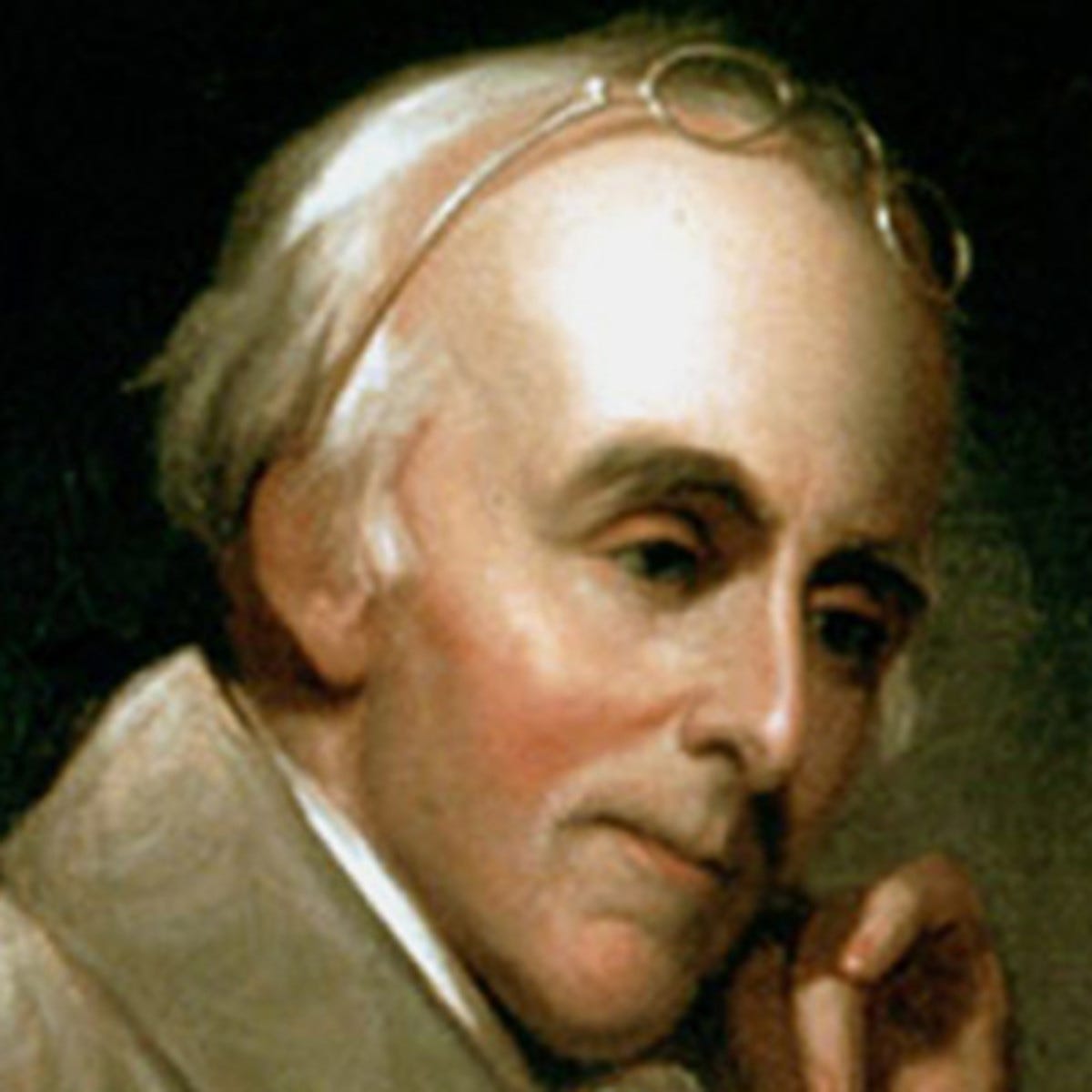

The generations preceding Lewis and Clark, and, indeed, several generations past, were virtually helpless in matters of health. Sudden death from disease or accident was common place and, therefore, expected. As Lewis was preparing for the journey that would be called the Corps of Discovery, President Thomas Jefferson sent him to Philadelphia to study under Dr. Benjamin Rush (1/4/1746 – 12/24/1813), the leading American medical authority of the day (and a signer of the Declaration of Independence in 1776). Captain Lewis and Captain Clark would be expected to care for the health needs of their men, as best they could.

As the captains were preparing to lead this band of men into the unknown, North America was plagued with a long list of diseases: measles, diphtheria, trachoma, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, malaria, smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, amoebic dysentery, dengue fever, typhus, leprosy, hookworm, mumps and venereal disease.

SMALLPOX

Lewis was most concerned about the men contracting smallpox and venereal disease. There was some discussion of having the men vaccinated against smallpox, but, in the end, no one was. The record doesn’t reveal why they didn’t vaccinate the men with the Kinepox (AKA Cowpox) vaccine available at the time, as an encounter with smallpox would certainly have doomed their venture. All members of Jefferson’s family had been vaccinated years earlier. So had Lewis. There was even some discussion of bringing the vaccine along with them to administer to the Indians.

Before they ventured west several epidemics of smallpox had decimated the Indian tribes along the very route they would travel. It is unclear if Lewis and Clark were aware of this in advance. The Arikara Indians had dealt with a bout of smallpox in 1780, and another several years before the Corps took off. Passing through their lands on & near the Missouri River, in present-day North & South Dakota, the Corps witnessed their deserted villages.

In 1781-82 smallpox also swept through Chinook Indian villages, at the mouth of the Columbia River in present-day Washington State, leaving behind abandoned villages and disrupted social structures. Lewis & Clark noticed pockmarked faces among the Chinook when they wintered over in 1805-06.

SERGEANT CHARLES FLOYD DIES

In the expedition’s fourth month they experienced their first and only death: Illness took Sergeant Charles Floyd, age 21, on August 20, 1804. Lewis diagnosed “Biliose Chorlick,” but he could do nothing for him. Indeed, even Dr. Rush could have done nothing to save Floyd. Based upon symptoms recorded in the journals kept by Floyd, Clark and Lewis, modern doctors believe Floyd died of a ruptured appendix.

Captain Clark took Floyd’s death especially hard as he was well acquainted with the Floyd family and had personally recruited young Charles. Floyd’s father had served under Clark’s older brother during the Revolutionary War. Clark was by his side and recorded in his journal that he died “with a great deal of composure.” He was buried with full military honors on a bluff near a small creek they named Floyd River.

VENEREAL DISEASE

Syphilis and gonorrhea had long been an accepted feature of military life, and Lewis knew that he would be treating it. His medical supplies included the standard treatments such as calomel and mercury. No cures were available, so improvement in symptoms was the best that could be expected. Mercury (pills & salve) was the main form of treatment, and was liberally used until the patient showed signs of mercury intoxication.

It was known that syphilis and gonorrhea were transmitted via sexual contact. Despite that, the captains allowed their men to mingle with Indian women. Their journals imply that neither Lewis nor Clark had sexual relations with Indian women; but, they didn’t discourage their men. It is unlikely they could have prevented all such mingling, anyway.

As the corps wintered over with the Mandan and Arikara Indians near present-day Bismarck, North Dakota, some husbands offered their wives to these visitors in hopes that the wives would acquire “special powers” which would, in turn, be transmitted to the husbands. As they traveled west Lewis ordered his men to give the Shoshone braves “no cause of jealousy” by having sex with their women without the husbands’ knowledge and consent. During their second winter, on the Pacific Coast south of present-day Astoria, Oregon, Clark recorded in his journal that Chinook women visited often “for the purpose of gratifying the passions of our men.”

MERIWETHER LEWIS, MIDWIFE

Sacagawea’s labor on February 11, 1805 was prolonged and difficult. Following advice from a crew member, Lewis crushed up a rattle from a rattlesnake and gave it to her with some water. He wrote in his journal “Whether the medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine . . .” Regardless, he further recorded in his journal “about five oClock this evening one of the wives of Charbono was delivered of a fine boy.”

TREATING INDIANS’ AILMENTS

Some of the Indian tribes viewed both Lewis and Clark as healers. A Mandan boy with frozen feet was brought to them. Frost bite was a common problem among soldiers, so both captains were experienced in treating it. When soaking his feet in water didn’t work, “Lewis took off the toes of one foot of the boy who got frost bit Some time ago,” according to Clark’s January 26, 1805 journal entry. Five days later the captains were forced to remove the toes on the other foot. The boy lived.

During their westward journey word spread among the Walla Walla and Nez Perce Indians (in present-day Idaho & Washington States) about medical treatments administered by both captains. Upon their return trek the following year eager patients traveled to their camps seeking medical care. Clark established quite a reputation among the Nez Perce: He noted in his journal “those two cures has raised my reputation and given those natives exolted opinion of my Skill as a phician. I have already received maney applications.”

The Nez Perce brought a chief to Clark, hoping he could help this man who had been quadriplegic for at least three years. While this is hard for modern Americans to believe, after several times in a “sweat pit” constructed pursuit to Lewis’s instructions, the man could use his hands and arms and “was much pleased with the prospect of recovery,” according to Lewis’ journal.

DON’T SCRATCH THAT ITCH

Mosquitoes and ticks were constant problems for the men, as were rashes and boils, “tumors and imposthumes.” Draining abscesses was usually sufficient to cure them. The men were constantly in and out of water, which was often muddy and filthy, and sometimes contaminated with animal carcasses and effluvia from Indian villages. The continuous abrasion of dirty clothes on dirty, wet skin, and the scratching of bites with filthy fingernails rubbed bacteria into the skin. The resulting rashes were the most difficult to treat. Dysentery was also common until the men learned to drink from deeper in the river and not from the surface.

Obviously, much has changed in the 200+ years since Lewis, Clark and crew trekked across our continent, twice.

I awoke this Christmas morning at 5:45AM. Pain in my right arm and shoulder * woke me, so here I am reading Diane’s very informative recount of the Lewis and Clark expedition. I had read the full account of this venture from the notes taken by these fabulous explorers. I recommend it highly as it is so full of detail.

Thanks to Diane for reviewing this journey. It is so appropriate for this Christmas Day of 2023.

*My discomfort probably is a result of my Journey to the golf practice range yesterday here at Seabrook Island, SC. At 86, I should probably limit my practice time to less than an hour. You’d think I would have learned that by now.

Let’s hope and pray for a better political climate Christmas Day 2024!